These are the words that Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger spoke just before the execution. Even when faced with death, he would not implicate Elizabeth, instead he used his scaffold speech to exonerate her and he may well have saved her life.

On the 11th April 1554, Sir Thomas Wyatt the younger was beheaded and then his body quartered, but what had led him to this sticky end? Rebellion is the simple answer.

Wyatt’s Rebellion

Wyatt’s Rebellion, or Wyatt’s Revolt, was an uprising which took place in 1554 and which nearly cost the 21 year old Elizabeth her life. Starkey writes of it:-

“It led to the most dangerous and difficult time of her life when she often feared imminent execution or murder. She even expressed a preference as to how she should die: like her mother, by the sword, rather than by the axe. The rebellion also threatened both Mary’s throne and her life. Which is why, in turn, her rage against Elizabeth was so deep and long-lasting.”

Wyatt had already shown his opposition to Mary when he supported Lady Jane Grey’s claim to the throne after the death of Edward VI – he escaped punishment that time – but he felt compelled to act when he found out about Mary I’s plans to marry King Philip II of Spain.

The plan was to have a series of uprisings in the South, South-West, Welsh Marches and Midlands, and then a march on London to overthrow the government, block the Spanish marriage, dethrone Mary and replace her with Elizabeth, who would marry Edward Courtenay. Unfortunately for Wyatt, other rebel leaders like the Duke of Suffolk (Lady Jane Grey’s father) and the ill-fated Lady Jane Grey (who had nothing to do with the revolt), the whole plan went pear-shaped. It flopped. It failed.

David Starkey, in “Elizabeth”, writes of how the government were alerted to the plots when Sir Peter Carew refused a summons to court and Ambassador Renard heard that a French fleet was assembling off Normandy. Courtenay was interviewed by his mentor Stephen Gardiner and blabbed everything. When the rebels learned that Mary knew of their plans, they did not give up, instead they decided to spring into action. Starkey writes of how three out of the four planned provincial revolts went ahead but were not successful as they “went off at half-cock”. However, Sir Thomas Wyatt did manage to raise a considerable “army” in Kent and Starkey says that “if Wyatt had pressed forward immediately resistance [in London] would probably have collapsed. But he delayed, giving Mary a chance to regain the initiative.”

Wyatt did not take advantage of the desertion of the City whitecoats and the confusion, he let this chance pass him by. Mary took her opportunity and rallied her troops. On the 1st February 1554, Mary gave a speech to the City government in the Guildhall, reminding them that she was England’s queen, that she was “wedded to the realm and the laws”, that she was the true heir to the throne, her father’s daughter, and that she loved her people. She said:-

“On the word of a prince, I cannot tell how naturally the mother loveth the child, for I was never mother of any. But certainly, if a prince and governor may as naturally and earnestly love her subjects, as the mother doth the child, then assure yourselves, that I being your lady and mistress, do as earnestly and tenderly love and favour you.” (From Foxe, Acts and Monuments VI, 414-15, quoted on p133 of Starkey’s “Elizabeth”).

She ended the speech by, according to witnesses, saying that:-

“She never intended to marry out of the realm, but by her council’s consent and advice. And that she would never marry but all her true subjects shall be content.” (from Machyn’s Diary quoted in Starkey).

This rousing speech and half lies worked their magic and won over the people. When Wyatt arrived at Southwark on the 3rd of February, he found it barricaded and guarded. Next, a few days later, he tried entering the City from Kingston and was successful. As they entered the City, the rebels split and although they were now at a disadvantage, having split into groups, a group of them still managed to scare off the Queen’s guards near the Holbein Gate. However, by the time Wyatt and his troops reached Ludgate, Mary’s force had gathered their wits and closed the gates. Mary’s troops far outnumbered the rebels and, with his men surrendering around him and no hope if winning, Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger surrendered and was captured. Wyatt was taken to the Tower of London.

The End

Not only did Wyatt’s Rebellion lead to his execution and the shadow of the axe hanging over Elizabeth’s neck for many months, it sealed the fate of Lady Jane Grey who had been kept in the Tower since Mary had seized the throne from her in July 1553. On the 12th February 1554, Lady Jane Grey and her husband Guildford Dudley were executed, a tragic end to Lady Jane’s short life and a frightening event for Elizabeth who knew she would be implicated in Wyatt’s Rebellion and who had a very shaky relationship with her half-sister, Mary.

Sir Thomas Wyatt was tried at Westminster Hall on the 15th March. He denied plotting the Queen’s death and would only admit to sending Elizabeth a letter to which she replied (though not in writing) “that she did thank him much for his good will, and she would do as she should see cause.” (Chronicle of Queen Jane and Queen Mary, ed. Nichols, quoted in Starkey). He did not implicate her in any other way. Wyatt was found guilty and sentenced to death but his execution was delayed for a time – it is thought that the Queen’s advisers hoped that Wyatt would still implicate Elizabeth in an attempt to escape execution.

On the 16th March, Mary’s advisers went to see Elizabeth to charge her with involvement in Wyatt’s Rebellion and to tell her that she would be taken to the Tower the next day. If you have read my post “The Imprisonment of Elizabeth”, you will know that Elizabeth used her famous “Tide Letters” as a delay tactic and was not taken to the Tower until the 18th March, Palm Sunday.

On the 11th April 1554, Sir Thomas Wyatt was led out to the scaffold. Starkey quotes Wyatt as saying on the scaffold:-

“And whereas it is said and whistled abroad that I should accuse my lady Elizabeth’s grace and my lord Courtenay; it is not so, good people. For I assure you neither they nor any other now in yonder hold or durance was privy of my rising or commotion before I began. As I have declared no less to the queen’s council. And this is most true.”

Between 9am and 10am, Wyatt’s head was severed from his body, his body quartered and his bowels and genitals burned. His head and the quarters of his body were then taken to Newgate where, according to Starkey, they were parboiled, nailed up and the head placed on a gibbet at St James’s. It is not known what happened to his head, as it disappeared from the gibbet.

Just over a month later, on the 19th May (the anniversary of her mother’s execution), Elizabeth was released from the Tower. She was not to enjoy complete freedom, as she would be kept for a while under house arrest, but she must have been so relieved to be free of the place where her mother had died and where Lady Jane Grey and Wyatt had died. Elizabeth must have said many prayers of thanksgiving.

We cannot be 100% sure that Elizabeth played no part in Wyatt’s Rebellion, as she had had contact with some of the rebels, so it is hard to know whether Wyatt was being truthful when he refused to implicate Elizabeth or whether he was being loyal to the woman who he saw as his true queen.

RIP Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger.

See yesterday’s post “RIP Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger” for a video on Wyatt and his rebellion.

Sources

- “Elizabeth” by David Starkey

I find it ironic that the son of the poet who loved Anne Boleyn rebelled against the crown in favor of Elizabeth.

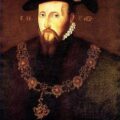

If that is a good likeness of him – What a noble face!

There’s another wonderful portrait of him at http://www.exacteditions.com/exact/browse/5/358/1335/3/51?dps=. He does look noble and very “alive” and real.

Dear Claire, What a good balanced article! Thank you.

Poor Sir Thomas Wyatt! I can’t help thinking that in any other country he would be regarded as a national hero and there would be all kinds of paintings by romantic artists showing him with his followers waving the flag at the barricades. If only somebody had told him that the English just don’t really do revolutions. War, yes, that’s OK – but if it affects business at home, not so good. He bought the fight to London, the capital city, the centre of trade and commerce, and that would never do.

He also did not have many properly trained soldiers at his command, and was outnumbered. Delays in having to drag his captured ships’ guns through the home counties and attack London from the West – after coming from Kent in the East – also contributed to his downfall. His men were simply exhausted by the time the fight commenced.

He was as you rightly say a very brave and decent man, standing up for what he and many of his fellow countrymen believed was right. Perhaps he should be just a little better-remembered and just a little better-regarded by history than he is at present.

Hi Claire,

I have looked at the other one by Holbein (I don’t know who painted the one you have shown) but I do prefer yours. However, the Holbein painting is really interesting and, for the time very realistic. I then looked at the Anne of Cleeves portraits, and if Mr. Holbein was true to his word, then A of C was not a bad looking woman. So was it the fact that she didn’t speak English, she didn’t wear the right clothes, or what made HVIII go against her so quickly when, if you think about her later life, she would have been an ideal wife for him – interested in her new country, willing to learn and highly intelligent.

Maybe Wyatt Jnr. was a romantic – His father certainly was and a great poet – an example to John Donne who wrote in the Elizabethan age and one of my faves of all time – But for all those romatics out there who loves poetry – please read “My Lute Awake” by Thomas Wyatt Senior. BUT have loads of hankies handy for the tears that will roll down.

I remember reading somewhere that Anne of Cleves had smallpox scars on her face which, of course, were not painted into the portrait by Holbein. That may be why Henry “liked her not.” I’d have to look, but I believe it was in the book by Kelly Hart, The Mistresses of King Henry VIII.

Love the portrait of Wyatt.

Great article.

I can’t help but thinking that if Wyatt did not lead a riot, Jane Gray and her husband might have survived and Elizabeth might have had less stress in her life because of all the questioning and suspicions that arose about her possible involvement in his plot. As the old saying goes, with friends like him, who needs enemies?

Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger is my 14th Great Grandfather on my maternal side, I gaze at his portrait because there is definitely a very close likeness to my brother who passed away in 2015 and as a youngster got in trouble for breaking out an old woman’s windows that were mean to his little sisters, irony