“We are more bound to them that bringeth us up well, than to our parents, for our parents do that which is natural for them, that is bringeth us into the world, but our bringers up are a cause to make us live well in it.”

On the 19th May 1536, Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, was executed as a traitor and adulteress. Just 11 days later, Elizabeth’s father, Henry VIII, married Jane Seymour and within two months of her mother’s death Parliament had confirmed that her parents’ marriage was invalid and that Elizabeth was illegitimate. Elizabeth went from pampered princess, the apple of her father’s eye, to ignored bastard. Elizabeth was so forgotten that her governess, Lady Margaret Bryan, had to write a letter to Cromwell begging for him to intercede with the King as Elizabeth had outgrown all of her clothes and her household had no money to buy more. J. L. McIntosh points out that “there is no evidence to suggest that Henry even saw his younger daughter from January 1536 until September 1542” and “thereafter, they encountered each other only during Elizabeth’s infrequent and short visits to court from 1543 until Henry’s death in 1547.”1 With her mother gone and her father intent on producing a legitimate male heir, Elizabeth’s household became her family.

But who made up her household? Who were the people who Elizabeth depended on in her childhood, the people she was talking about when she said “we are more bound to them that bringeth us up well, than to our parents”?

Lady Margaret Bryan

Lady Margaret Bryan acted as governess to all three of Henry’s legitimate children: Mary, Elizabeth and Edward. She was a former lady-in-waiting to Mary’s mother, Catherine of Aragon, and became Mary’s governess at her birth in February 1516. She left Elizabeth’s household in 1537 on the birth of Prince Edward, the future Edward VI.

Lady Bryan was related to Anne Boleyn by marriage. After the death of Lady Bryan’s father, Sir Humphrey Bourchier, her mother, Elizabeth Tilney, married Thomas Howard, the 2nd Duke of Norfolk, and the couple had children, including Elizabeth Howard, Anne Boleyn’s mother, thus Lady Bryan became an aunt to Anne Boleyn and was connected to the powerful Howard family.

Lady Bryan has two children by her second husband, Sir Thomas Bryan: Elizabeth Bryan and Sir Francis Bryan. Elizabeth married Sir Nicholas Carew, a man known for being involved in the downfall of Anne Boleyn and for mentoring Jane Seymour, and Francis was nicknamed “The Vicar of Hell” by Cromwell, a suitable nickname for one who was happy to make use of his cousin, Anne, when she was in favour, and who then abandoned her to the wolves.

Sir John Shelton

Sir John Shelton was married to Anne Boleyn, sister of Thomas Boleyn and aunt to Queen Anne Boleyn. The couple were in charge of the households of Mary and Elizabeth from 1533 and were the parents of Margaret and Mary Shelton, maids-of-honour to Anne Boleyn. Sir John was the steward of Mary and Elizabeth’s combined household and was, therefore, in charge of expenditure and keeping the accounts. Lady Anne Shelton was one of the ladies appointed to serve Anne Boleyn during her imprisonment in the Tower in 1536.

In “From Heads of Household to Heads of State”, J. L. McIntosh, writes of how, during the crisis in Elizabeth’s household after Anne Boleyn’s execution when money from Cromwell was not forthcoming, Shelton “most likely authorized a Ralph Shelton (presumably a relative) to set up a poaching scheme involving several of the

steward’s servants in the parklands surrounding Hatfield. No wonder Elizabeth’s high table had such “dyvers metes.” “!2

In 1537, John Shelton was replaced as steward by William Cholmely, and in 1539 Shelton died. However, his family remained important to Elizabeth throughout her life. She visited them on numerous occasions and Shelton’s granddaughter, Lady Mary Scudamore, was a member of Elizabeth’s Privy Chamber when she was queen.

William Cholmely

William Cholmely had been Mary’s steward and cofferer after she had returned from the Welsh Marches in 1527 and it was he who took over from Sir John Shelton as steward of the combined household of Mary and Elizabeth in 1537. J L McIntosh writes of how Cholmely is referred to as the “late cofferer” in Henry VIII’s Privy Purse Expenses 1538-1541 “suggesting that he had died or had moved on to another post by 1538”3.

Katherine Champernon (Kat Ashley)

Katherine Champernon (or Champernowne) was appointed to Elizabeth’s household in July 1536 and became her governess in 1537. Elizabeth knew her as “Kat” and later said that she took “”great labour and pain in bringing of me up in learning and honesty”. Kat, who married Sir John Ashley in 1545, was a close confidante to Elizabeth and was appointed First Lady of the Bedchamber when Elizabeth became queen.

Kat was highly educated and seems to have been in charge of the princess’ education between 1536 and 1544.

You can find out more about her in Finding Kat Ashley and Elizabeth and the Two Katherines.

Trivia: Kat’s loyalty to Elizabeth was tested when she was arrested and imprisoned in 1549 on charges of being involved in Thomas Seymour’s plan to marry Elizabeth. She refused to implicate her mistress and was released after a few weeks.

John Ashley

J L McIntosh writes of how John Ashley, Kat’s future husband, joined Elizabeth’s household sometime before 1540. Like the Sheltons and Lady Bryan, he was also a Boleyn relative. Ashley’s mother, Anne Wood, was the sister of Lady Elizabeth Boleyn whose husband, James Boleyn, was the brother of Anne Boleyn’s father, Thomas Boleyn. Although this seems a rather tenuous family tie, McIntosh makes the point that it was important to Elizabeth and that on his arrest in 1549, during the Thomas Seymour crisis, Elizabeth asked for his release “for he is my kinsman”.

On Elizabeth’s accession, Ashley became Master of the Jewel House and Treasurer of Her Majesty’s jewels and plate.

Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy

There is some evidence that Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy, replaced Lady Bryan as the Lady Mistress of Mary, Elizabeth and Edward and that she was with Elizabeth until she retired in 1545/1546. In an article “Lady Troy and Blanche Parry: New Evidence about their Lives at the Tudor Court”4, Ruth E. Richardson, says that a letter from Sir Robert Tyrwhitt states that Lady Troy had trained her niece, Blanche Parry, to be her successor, as head of the household, but that the position was actually given to Kat Ashley and Blanche was made the second gentlewoman of Elizabeth’s household. Blanche Parry became the chief gentlewoman on Kat’s death in 1565. The article also says:-

“That more documentation has survived about Kate Ashley due to her periods of imprisonment has, in fact, unbalanced our perceptions of the household personnel. It was Lady Troy and Blanche Parry who were also instrumental in providing a stable and happy childhood for Elizabeth and Edward.”5

Blanche Parry

Ruth E. Richardson writes of how both of Blanche’s epitaphs, the one on her tomb at St Margaret’s Church, near Westminster Abbey, and the other at her monument at Bacton in Herefordshire, state that she served Elizabeth from birth. The St Margaret’s epitaph describes Blanche as Chief Gentlewoman of Elizabeth’s Privy Chamber and Keeper of the Queen’s Jewels and the Bacton Epitaph, which was composed by Blanche herself, talks of Blanche seeing Elizabeth’s cradle rocked and remaining the Queen’s servant until her death. Richardson concludes that “the evidence from the Bacton epitaph suggests that once Blanche entered the service of the baby princess until her death fifty-six years later, she was in almost daily contact with Elizabeth.”6 She must have been a real mother figure to Elizabeth.

You can read more about Blanche in Ruth E. Richardson’s article “Lady Troy and Blanche Parry: New Evidence about their Lives at the Tudor Court” and in “Mistress Blanche”.

Thomas Parry

Thomas Parry was a friend and relative of William Cecil and, like his relative Blanche, joined Elizabeth’s household when she was a child. McIntosh states that it is unknown exactly when he joined the princess’ household, but that it was definitely before 1547 and “probably well before then”. He was Elizabeth’s “cofferer” (or treasurer) and while Kat Champernon was in charge of Princess Elizabeth’s privy chamber, Parry dealt with the household accounts.

Parry was also connected to the Boleyns. His wife, Anne Reade, was the widow of Sir Adrian Fortescue, whose mother, Alice Boleyn, was an aunt of Queen Anne Boleyn.

Parry, like Kat Ashley, was detained in 1549 for his alleged involvement with the Seymour scandal. Although he had said “I had rather be pulled with wild horses than I would [disclose it]”7, once in the Tower he did talk of Elizabeth’s feelings for Seymour, but although he may have let his mistress down then he did not let her down during her house arrest at Woodstock.

At Woodstock, Elizabeth was under the supervision of Sir Henry Bedingfield who had been told to remove Thomas Parry from his position as head of the household accounts. However, Bedingfield did not want to take financial responsibility for the household so he allowed Parry to take lodgings at the local inn so that he could continue with his job but still be separate from Elizabeth and her staff. The result, as David Starkey points out, was that Elizabeth and Parry “ran rings round him [Bedingfield] and often barely bothered to disguise the fact.”8 Elizabeth’s servants would visit Parry at the inn, on the pretext of discussing household business with him and instead gather information from him to update their royal mistress on what was going on in the world outside her prison. Parry was also able to keep Elizabeth’s political connections alive and act as a go-between and messenger for his mistress. David Starkey also writes of how Thomas Parry worked at keeping Elizabeth’s landholding intact and maintaining management control, making sure that rents were paid and the stocks of deer on her lands were protected while she was under house arrest. Without Parry looking out for her interests, Elizabeth’s tenants could have revolted.

Thomas Parry’s hard work and loyalty were rewarded by Elizabeth when she became queen. On her accession she knighted him, made him the Controller of the Household and appointed him to her Privy Council.

Wiliam Grindal and Roger Ascham

Elizabeth was educated by Kat Ashley (who had advice from Roger Ascham) until 1544 when the Humanist and Protestant, William Grindal, became Elizabeth’s tutor. Grindal was part of a circle of men who were all part of the influential Humanist movement at Cambridge University. This group included the likes of Matthew Parker (Anne Boleyn’s chaplin), John Cheke (Edward VI’s tutor), Anthony Cooke, Roger Ascham (Elizabeth’s future tutor), John Dee and William Cecil – all men who played a part in Elizabeth’s life (see The Cambridge Connections).

William Grindal died in 1549 and his position as Elizabeth’s tutor passed to Roger Ascham who continued what Grindal had begun, i.e. ensuring that Elizabeth’s education was a Protestant one and was of the “new learning”.

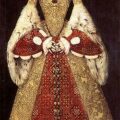

Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr married Elizabeth’s father in July 1543, becoming Elizabeth’s stepmother. Although Elizabeth lived in her own household, she became close to Catherine and shared her Protestant sympathies. After her father’s death in January 1547, Elizabeth carried on visiting Catherine and eventually moved into her Chelsea home. Unfortunately, Catherine’s new husband, Thomas Seymour, took a shine to Catherine’s new charge and started a

The Influence of Anne Boleyn

J.L. McIntosh writes:-

“The presence of these Boleyn relations and the evidence of Queen Anne’s interest in the material splendor of her daughter’s environment indicates that Anne, before her death, was an important, if indirect, early influence on the development of her daughter’s household’s culture. Henry VIII funded the household and had the final say in all important aspects of his daughter’s upbringing, such as when she was weaned, but it was Anne who was guiding the routine behavior and agenda of the household. She instructed her relative, Anne Shelton, to ensure that Mary—when living in the conflated household in 1534—did not attempt to usurp Elizabeth’s status by claiming the princely title. By installing her relatives and supplementing Henry’s expenditure on the household with her own purchases of lavish clothing for Elizabeth, Anne was attempting to ensure that Elizabeth would receive the treatment due to a princess and heir to the throne. The queen also may have begun to draw up plans for Elizabeth to receive a Protestant humanist education.”9

Although Anne was unable to bring her daughter up, she made sure from the start that her daughter was well taken care of and had the appropriate household for a royal princess AND on the 26th April 1536, shortly before her downfall, Anne Boleyn spoke to her chaplain, Matthew Parker, one of the Cambridge set of men I have already mentioned, and asked him to to ensure that Elizabeth was looked after if anything happened to Anne. By instructing Parker in this way, Anne was not just ensuring that Elizabeth’s spiritual needs would be met, she was also making sure that Elizabeth would have the connections she needed to become a formidable woman and queen, and we all know that Elizabeth did go on to depend on men like John Dee and William Cecil.

The Power of Elizabeth’s Household

In “From Heads of Household to Heads of State”, J.L. McIntosh concludes that “without their households, there is reason to doubt that either princess could have acceded to the throne” and writes of how it was their “elite households” which allowed Elizabeth and her sister, Mary, to succeed to the throne successfully “in spite of rival male claimants, their own statutory illegitimacy, their gender-based subordination, and the hostility of incumbent monarchs like

Henry VIII and Edward VI” and that they were able to take advantage “of the opportunities available to them as heads of household and landed magnates.” They were powerful women with influential people behind them.

Elizabeth relied on her household for support, both emotionally and politically, for advice, for affection and friendship, and for protection. They were the family that she never had and they helped her to become the well-rounded individual that she became, the confident woman who faced many challenges and even the threat of death. Like parents, they were willing to do anything they could to protect her, to even put their own necks on the line, and Elizabeth loved them for it and rewarded them accordingly.

I find it interesting that many of Elizabeth’s household had connections with the Boleyn family and I’m sure that in the privacy of her home Elizabeth would have had the freedom to ask them about her mother. What do you think?

Notes and Sources

- From Heads of Household to Heads of State: The Preaccession Households of Mary and Elizabeth Tudor 1516-1558, J.L. McIntosh, Chapter 2

- Ibid., Chapter 1

- Ibid., Notes on Chapter 1

- Lady Troy and Blanche Parry: New Evidence about their Lives at the Tudor Court, Ruth.E. Richardson, 2009

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Elizabeth, David Starkey, p73

- Ibid., p157

- McIntosh, Chapter 2

Hi Barbara,

There is no evidence to back up these myths and you can read more about them at https://www.elizabethfiles.com/the-old-myths-regurgitated-the-bisley-boy-and-more/4697/

Christine says:

Who were the rival male claimants??? Elizabeth’s survival through Mary’s reign may have been greatly assistedby her household but hardly her accession. When Mary Tudor lay dying, England was in war with France and part of the Habsburg interest, so Mary Stuart was out of the question. With her on the English throne England would have become practically French and Philip II would never have allowed this to happen. So the “bastard” Elizabeth was the only choice left.

Just answering your question a tad late. Elizabeth’s great- grandfather (Edward IV) had lots of children with his wife Elizabeth Woodville. Although the surviving children were all female, they produced males that were canadatesfor the throne during Elizabeth’s ascension.

Please. Have you heard of Louis de Boleyn governor of the Bastille, who bought a Castle on 1460 near Paris on the road to Provins. Was he an uncle of Thomas Boleyn? On 1520 the same castle was owned by Lady Marguerite Herbert who married Lord Jacques Du Moulin. Someone said that Marguerite Herbert was an aunt of Ann Boleyn. What was the link with Blanche Herbert Lady of Troy? Sorry for my english

Hi I thought you guys would be interested to here about the research into my family tree.

My line comes from Joan Acworth Bulmer a lady in waiting to her cousin Catherine Howard.

Since I got all the records out of our family I am fascinated to learn that one of Joans daughters Mary Kighley Waldegrave/Acworth marries Isac Astley I have only found this out last 2 weeks im gobsmacked say the word.

Isac Astley marries Mary which links my family to the Boleyns how cool is that?.

As it stand John Astley is my second cousin removed once ,his mother is Anne Wood sister to Elizabeth Boleyn wow fucking wow sorry for the swearing lol.Joan Acworth was pardoned after the execution of Catherine in 1542.

10 months later she Joan marries Edward Waldegrave whos father was sheriff of Norfolk.

Joan dies at the age of 70 and is buried in Lawford Church Lawford Essex she once lived at Lawford Hall with Edward.

It gets better what we have since found out Joans father George Acworth an Mp from Toddington was issued a writ in 1526 but the 3rd duke of Norfolk stole it along route giving the title as baron or duke to the Norfolk family this is fraud in itself and that title should have been hnded down my side of the family making my dad the proper duke of Nofolk we are 5 families higher than the current duke.